The Children of Jordanian Women: Citizens without Real Citizenship

Translated by Nathaniel Moses

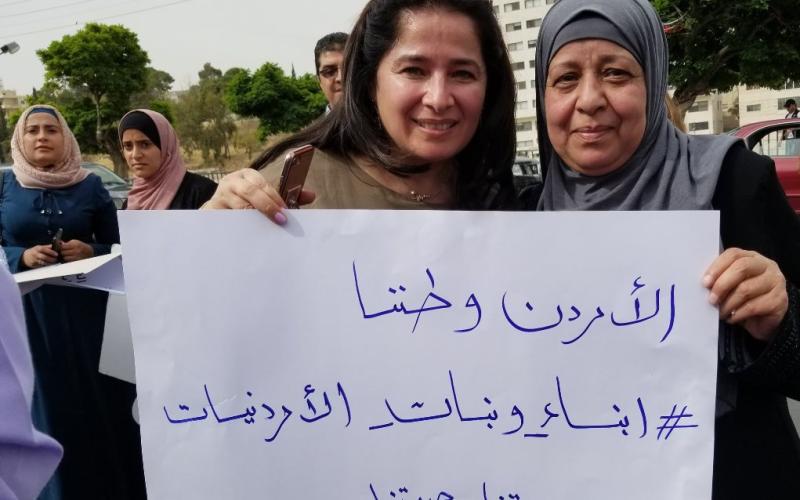

“My mother is Jordanian and her nationality is my right. I am a Jordanian woman and I will not stop demanding my right to pass my nationality on to my children. Jordanians are equal under the law.” Such were the slogans calling for the rights of the children of Jordanian women married to non-Jordanians.

The Constitution and Nationality

Article 6 of the Jordanian Constitution states that “Jordanians are equal before the law. There shall be no discrimination amongst them in rights or responsibilities, whether based in race, language, or religion.”[1]

Constitutional amendments have been drawn up and implemented following the 2022 publication of the Jordanian Constitutional Amendment Project in the official newspaper (no. 5770). The fourteenth amendment of the 1952 Jordanian Constitution introduced twenty-five articles as well as the words “Jordanian women” to the second section of the Constitution, rendering it “the rights and responsibilities of Jordanian men and women” in accordance with the ratification of both the Senate and House of the National Assembly in early 2022.[2]

The Jordanian National Charter further affirmed this right in stating that “Jordanian men and women are equal before the law. They shall face no discrimination in rights or responsibilities, nor shall they be discriminated against on the basis of race, language, or religion.[3]

Amal is a Jordanian woman and mother of four children whose husband does not hold Jordanian citizenship despite residing in Jordan since birth. She relates the challenges facing her family. “I am Jordanian and I benefit from all of the national rights to the same extent as Jordanian men. However, when it comes to education, we must pay non-Jordanian university fees. Regarding healthcare, my children cannot be treated in public hospitals like Jordanians.”[4]

The Law of Nationality

The Association of the Jordanian Women’s Solidarity Institute, “Tadamun” notes that Jordanian nationality is defined according to the Jordanian Nationality Law and its 1954 amendment (no. 6).[5] This law defined the instances in which someone is considered Jordanian, especially in articles 3, 8, and 11. Article 9 of this law states, “The children of Jordanian men are Jordanian wherever they are born.” Meanwhile, the children of Jordanian women are not stated here to be Jordanians wherever they are born, namely in instances of marriage to non-Jordanian men. The law allows non-Jordanians to acquire Jordanian citizenship through a naturalization request governed by the legally stipulated regulations.[6]

The Text is Unconstitutional

The lawyer and women’s rights activist Inam Al-Asha notes that certain laws are unconstitutional following the process of amendment. “The Constitution represents the highest summit of the legal hierarchy, and it is of fundamental importance that laws of lesser importance do not contradict it. However, following the constitutional amendment certain laws were rendered unconstitutional… This means that any law which contains discrimination, bias, or gender inequality must be reconsidered.”[7]

Statistics

The number of children of Jordanian women married to non-Jordanians is not known precisely as there are no recent figures on their numbers in the Kingdom, as mentioned in a report issued in 2018 by Human Rights Watch, a non-governmental and non-profit human rights organization. The Ministry of the Interior announced in 2014 that there are more than 355,000 non-Jordanians born to Jordanian mothers and non-Jordanian fathers.[8]

Services and Privileges

Leith is the alias of a 19-year old whose mother is Jordanian and father is from Gaza. Expressing his concern, he states “I possess a provisional passport issued to the ‘descendants of Gazans’ and I was issued a card reflecting my status as the child of a Jordanian mother, however this does not mean that my nationality is Jordanian, despite my not knowing any nation other than Jordan. When I traveled abroad, I was considered Jordanian. Everyone treats me as Jordanian. I competed for educational opportunities with Jordanian students. We face challenges in all aspects of life. I am thinking of emigrating in order to acquire a nationality as I cannot acquire a nationality via my mother.[9]

The Human Rights Watch report added that in 2014, following numerous demands from Jordanian women married to non-Jordanians regarding their children, articulated in the form of campaigns and sit-ins such as the “My Mother is Jordanian” campaign and the “My Family’s Rights” coalition,[10] the government introduced a number of privileges and concessions by way of a cabinet decision. Among the guaranteed privileges awarded by the government is a recommendation to issue identification cards to the children of Jordanian women married to non-Jordanians. The relevant authorities issued up to 72,000 identification cards to the children of Jordanian women in 2018. However, approximately 80% of all children of Jordanian women did not obtain them. Without obtaining identification cards they cannot apply for relevant benefits.[11]

Amal added, her words filled with anxiety, “The identification as ‘children of Jordanian women’ was useless. I remember one time entering the hospital and my children could not donate blood to me[12] seeing as they are not Jordanian, despite having obtained the status of ‘children of Jordanian women.’”

Mohammed, a 22-year-old son of a Jordanian mother describes the privileges bestowed upon them. “We children of Jordanian mothers feel that we have been unjustly deprived of our rights. The fundamental right [to citizenship] stipulated in the Jordanian Constitution has been turned into a piece of yellow plastic which cannot satisfy our hunger and which provides us access to benefits whose administration has been left to the whims of bureau employees.

International Agreements and Universal Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “All are entitled to enjoy all of the rights and freedoms enumerated in this Declaration without any form of discrimination on account of race, color, gender, language, religion, beliefs whether political or otherwise, national origin, social status, class, birthplace, or any other status. And Article 15 of the Declaration grants all individuals the right to a nationality.[13]

The solution lies in giving the right of citizenship to children of Jordanian women for the enjoyment of all civil and political rights, according to Riyad Al-Sobh, a human rights consultant.[14]

Jordan is obligated not to discriminate against women according to the International Treaty on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in article 9, clause 2 which states, “state parties shall grant women rights equal to those of men with regards to the citizenship of their children.”[15]

Citizenship and Anti-discrimination

A 2019 study published by the Information and Research Center of the King Hussein Foundation states that “discrimination in matters of nationality is among the most pressing issues of gender-based discrimination facing Jordan.”[16]

The United Nations describes gender-based discrimination as: “includ[ing] any distinction, exclusion or restriction due to gender that has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms. Direct discrimination occurs when a difference in treatment relies directly on distinctions based exclusively on characteristics of an individual related to their sex and gender, which cannot be justified on objective and reasonable grounds (e.g. laws excluding women from serving as judges). Indirect discrimination occurs when a law, policy, programme or practice appears to be neutral but has a disproportionately negative effect on women or men when implemented (e.g. pension schemes that exclude, for instance, part time workers, most of whom are women).[17]

Upon inspection of the 2021 special annual report of the Office of Civil Status and Passports we see mention of the naturalization of wives in the section detailing nationality procedures and no mention of the naturalization of the husbands of Jordanian women or their children.[18]

Incidence of Divorce According to Nationality of the Divorced[19], [20]

Marriage between Jordanian women and non-Jordanian men without the existence of laws protecting their children and granting them their mothers’ nationality adds hardship to their lives and those of their families as well as financial and social burdens and sometimes domestic problems that may lead to divorce and the fragmentation of the family.

Nationality | 2020 | 2021 |

Palestine | 183 | 241 |

Egypt | 46 | 77 |

Syria | 53 | 64 |

Saudi Arabia | 22 | 49 |

Iraq | 172 | 26 |

United States | 4 | 19 |

Other Nationalities | 51 | 78 |

Total | 376 | 554 |

Privileges Unprotected by Law

Jordanian women have not attained full rights as Jordanian men have. Rather, Jordanian women have attained certain privileges unprotected by law, such that they can be repealed at any time by those who granted them.

Of course, these severe restrictions and limitations placed upon this right leads to negative repercussions for the social and professional life of the families and the children. Most of them continue to suffer in renewing their residency permits, acquiring work licenses, health insurance, and public education, in making purchases and investments, and even in acquiring driver’s licenses. By and large, and because decisions of the cabinet cannot replace existing laws and regulations, Jordanian government bodies continue to subject them to the same rules and regulations governing the provision of services to non-citizens according to the Human Rights Watch report.[21]

Jordanian Citizenship Does Not Contradict the Right of Return

The Human Rights Watch report states that “the majority of Jordanian women married to foreign nationals are married to Palestinians who have not obtained Jordanian citizenship and who experience unique legal conditions in Jordan. Therefore, the main argument of politicians and local authorities against repealing this discriminatory policy is the claim that repealing these laws would undermine efforts to establish a Palestinian state and would alter the demographic balance in Jordan.”[22]

According to the statutes of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951, naturalization strips the refugee of his legal status as a refugee. However, this does not apply to Palestinian refugees for whom naturalization in any country does not remove their refugee status. Palestinian refugees have a different legal status under international law and they are even exempted from the Convention of 1951 which states that “The Convention does not apply to those refugees who benefit from the protection or assistance of a United Nations agency other than the UNHCR.”[23] As is well known, this refers to no other than the Palestinian refugees who are registered by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).

“The Right of Return is a foundational and permanent right which cannot be waived or conceded.” This was guaranteed by United Nations Resolution 194 of 1948 and was recognized by human rights conventions and the right to self-determination.[24]

The fears used by the government to justify their position prevent women from acquiring the right to be treated as equals with men in passing citizenship on to their children.

Amal concludes, saying “we are still waiting for the application of decisions that grant us this human right and realize our children’s hope to live with dignity.

This report was prepared with the support and patronage of the Center for the Protection and Freedom of Journalists.