Awaiting Their Tablets… Unable to Access the e-Platform

Report by: Huda Hanayfeh

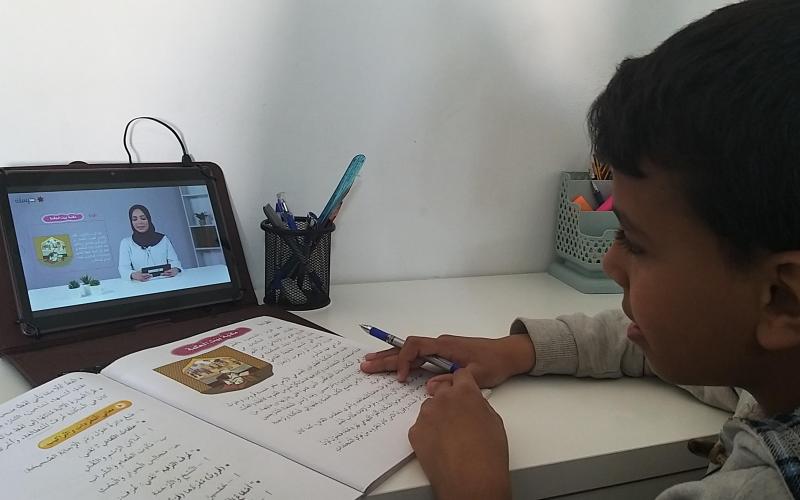

When I asked seventh grader Mohammad how he follows up on his school work amid the conditions imposed by the pandemic, he said: “I am so upset! We have missed out on so much school because of Corona. At home we have no internet or even an adequate cell phone. All my friends who live on the same street can access the (Darsak) platform simply because they have internet.” Mohammad attends Um Qusair Elementary School in Al Mugablain, part of the district of Quwaismeh. He sat next to me as I spoke to his mother about the reasons why Mohammad and his siblings were not attending school.

I was warmly welcomed by the 30 year old mother of five orphans in her rented home in a poor neighbourhood in Al Mugablain. Mohammad’s mother could not pursue her education after high school. She seemed embarrassed by the simple furniture of her home which comprised of a few floor mattresses covering one fourth of the room’s overall area. In a sad voice she said: “My heart aches for my five school-aged children. They learned nothing during the first semester. Nothing at all.” Her youngest daughter, Hiba, is in first grade, while her eldest daughter, Nada, is in fourth grade. Like their siblings, both girls have missed out on schooling since the beginning of the first semester. Nada says: “The only devise we have at home is my mother’s cell phone, which is disconnected. My classmates attend classes and submit assignments, and I wish I could be like them.” She directed her words at me hoping I would have a magical solution to the problem.

The family’s dilemma began when in-class education was suspended due to the outbreak of the pandemic. Defence Order No.1 was issued on March 17, 2020, granting the Prime Minister absolute authority to suspend or execute any decision as deemed in the country’s interest during the state of emergency. Soon after, the Ministry of Education announced that it will turn to a distant electronic learning system as stipulated by Defence Law No. 7, and later launched the e-platform (Darsak) on the 22nd of the same month. Accessing the platform would require an internet connection in addition to up-to-date cell phones, tablets or laptop computers. The ministry was aware that these requirements were not available to a large number of students. An article published on the website of the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship on August 23, 2020 stated that “studies have shown that 12-16% of Jordanian public school students do not own devices that are connected to the internet, hence, the government has decided to cover the cost of purchasing tablets and distribute to underprivileged students according to a fair criteria.” The number of students in Jordanian public schools is around 1.5 million, which means that according to the above percentage, over 180 thousand students were most probably deprived of attending any classes through (Darsak) platform.

Tens of thousands of Jordanian students face the same problem as Mohammad and his siblings. In an attempt to show the extent of this problem and its implications on the educational level of students, this report will shed light on the situation of some students in Al Mugablain who have been unable to attend school lessons through the (Darsak) platform.

3800 Tablets So Far

The above mentioned government decision indicated that “the tablets would be purchased in instalments” and that “the tenders committee in the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship has been mandated to proceed to negociate, contract and procure 160 thousand tablets that will be distributed among students mid-January of 2021, which is after the end of the first semester of the 2020/2021 school year.

The invitation to tender was officially announced in August of 2020, according to the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship’s spokesperson Shurooq Hilal, who added that “tablets will be handed over to the Ministry of Education at the scheduled date.” Hilal also said that both the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Digital Economy responded to cases where tablets were urgently needed which led the former to expedite the distribution of 3800 tablets, donated by independent individuals and institutions, among the most underprivileged students in various directorates. Hilal added that there should have been a separate independent tender for the purchase of a smaller number of tablets for a certain category of students.

On May 31, 2020, the Ministry of Education received 1591 tablets from the Crown Prince Foundation, and in December of 2020, it received another donation of 7500 tablets from the Department of Statistics. In a statement published on December 5 on Al Mamlaka Channel’s website, the ministry’s spokesperson, Abdul Ghafour Al Quraan, said: “So far, 3176 tablets have been distributed in several districts.” We asked the ministry a few questions regarding the number of donated tablets, the number of eligible students and the criteria upon which the tablets were distributed, especially in the district of Al Quwaismeh. The answers given by the ministry were general in nature and did not contain any actual figures which drove us to seek information from the data published in various media sources.

In an official statement, the Ministry of Education said it had “allocated areas that lacked internet service and families who were financially unable to provide their children with tablet devices, and launched parallel initiatives to supply these tablets in cooperation with several governmental institutions and with the support of the private sector.” It added that “the ministry is vigilant in ensuring that the tablets reach eligible underprivileged students who often reside in remote areas of the Kingdom, and that the ministry’s directorates are responsible for determining their eligibility in cooperation with schools who are more informed of their situation on the ground.”

Directorate Conditions

On May 28, 2020, Al Quwaismeh Education Directorate issued an official memo to all its schools to list the names of students in need of tablets, and, according to Amal Suwaity, Headmistress of the Hassaniah Elementary School for Boys, issued a similar memo on November 22, 2020 asking all school superintendents to provide the directorates with a list of underprivileged students who had no income, no access to distant learning devices, whose parents receive aid from the National Aid Fund, families with three or more children in school and orphaned students with no form of support.

According to the spokesperson for the Ministry of Social Affairs, Najeh Sawalha, the National Aid Fund supplied the Ministry of Education with a list of benefiting families to provide them with tablets. The number of eligible families in Al Quwaismeh was 958, of which 310 resided in Al Mugablain.

During the preparation of this report, the Ministry of Education’s spokesperson, Abdul Ghafour Al Quraan, stated that the ministry had supplied the schools in Al Quwaismeh district with 85 tablets only.

Head of the Department of General Education and Student Affairs in Al Quwaismeh’s Directorate of Education, Essam Khlaifat, stated that the directorate had supplied the ministry with the names of 415 eligible students and on May 28, 2020, actually received 83 tablets from three donating entities, the Crown Prince Foundation, the Queen Rania Centre for Education and Information Technology, and Al Quwaismeh district municipality. However, only the tablets donated by the Crown Prince Foundation contained internet chips, according to Khlaifat.

Mohammad’s mother receives JD 200 monthly from the National Aid Fund, from which she pays JD 150 for rent and what is left she spends on food. She says: “Food is more important than internet access.” Still, when she became aware that the Ministry of Education intended to supply underprivileged students with tablet devices, she visited the school of her daughters, Hiba and Nada, in November of 2020, to inquire about her daughters’ eligibility and was assured by Hiba’s teacher that they qualify to receive a tablet. Yet days and months have passed without any progress. She adds: “My children have missed out on a whole semester of school while waiting for the promised tablets. If only officials could pay us a visit and see our situation for themselves, or at least allow us to return to in-class education.”

Mohammad and his siblings managed to follow up on their lessons through special television educational programming, but to pass the semester and sit for exams, they were required to log into the e-platform which made studying confusing and complicated, leading them to eventually give up.

Hiba’s teacher, Asma’ Khalil, says: “Hiba has not attended classes through the platform since the beginning of the semester. In addition to my being a teacher, I live close to her and am fully aware of her family’s difficult financial circumstances. Hence, I have added her name to the ministry’s list of qualifying students but unfortunately neither Hiba nor any other eligible student in the school have received the promised devices.”

Sixth grader, Amal, is another student who lives in the same neighbourhood and who has been unable also to attend classes through the (Darsak) platform. Her aunt describes the family’s circumstances saying: “They live in a rented house, with an absent father who lives in another country with his second wife and the mother work here as a house cleaner. I tried to help as much as I could but the cost of the internet bundles she needed was too much. I also have school aged children and cannot afford internet costs for everyone. Therefore, I helped her to study from her school books only.”

Expected Outcomes

Teachers fully understand this dilemma since they form the main link between the student and the educational process. They are also aware of the extent of the negative impact this problem will have on students. Aziza Mubarak, an Arabic language teacher at Al Hassaniah Elementary School for Girls states: “I feel sad for all those with no access to in-class education, as this will definitely cause a gap in their educational journey. With the end of the first semester, many parents still did not have the financial means to provide their children with the devices required for distant learning, which deprived these students of a basic right to live in dignity.”

Maha Hamdan, an Arabic language high school teacher in Al Mugablain, explains another side of this problem saying: “I listed the names of all my underprivileged students, although some of them did not fully fit the criteria set by the ministry. Unfortunately, not one single tablet has reached our school.”

The headmistress of Al Hassaniah Elementary School for Boys, Amal Al Suwaity, along with several teachers, took the initiative to help students instead of waiting for solutions from outside. Al Suwaity says: “The criteria set by the ministry did not apply to most of the underprivileged students in our school. Therefore, we made our own record for students who were unable to access the e-platform, and some teachers donated internet cards to several of them since we were fully aware of their circumstances. Only three students in the school were eligible according to the ministry’s criteria. Nevertheless, we still have not received any tablet.”

Tayseer Al Hoor, teacher of Islamic Education in the public schools of Um Qusair and the second Mugablain Elementary School for Boys says: “The absence of some students from the e-platform is expected and understood since we live in a society where owning the required devices is beyond the financial means of many families. Even if a family were to own a laptop or tablet, how would this device be shared to access the platform if they had six children in school?!” He added that the schools where he works have not received any tablets yet, and that students in these schools have not received any financial help to overcome this problem.

Regarding the size of his interaction with students on the platform, Al Hoor says: “I have observed that student response to homework assignments does not exceed 33%. This is in addition to the fact that the technical problems students face when attempting to access the platform also impact their interaction. Hence, distant learning cannot suffice alone as a means of education, as it lacks a basic pillar, which is the variation of teaching strategies, especially in elementary grades which require more one-on-one interaction between teachers and students.”

Justice in Education

In his speech before the Jordanian parliament on November 26, 2020, the Minister of Education made no mention of students who could not access the platform, and stated that 88.5% of Jordanian students actually accessed the platform and that 62% of these students registered daily on the platform and regularly attended their classes. The minister considered these figures to be quite satisfactory.

In an attempt to explain the ministry’s delay in distributing the tablets among eligible students, the Secretary General of Administrative and Financial Affairs at the ministry, Najwa Qubailat, said that “donors may place conditions on their donations. For example, some may request that we distribute their donated tablets in remote villages in the south, while others may request that their donated devices be distributed among the children of families benefitting from the National Aid Fund.”

Dr. Fakher Daas, is a human rights activist and member of the National Campaign for the Rights of Students “Thabahtouna,” (Arabic for you have slaughtered us) launched in 2007. He considers the figures stated by the minister as proof of “the government’s failure to achieve justice in education” and a violation of Article 6 of the Jordanian Constitution which stipulates that “The Government shall ensure work and education within the limits of its possibilities, and it shall ensure a state of tranquillity and equal opportunities to all Jordanians,” in addition to Article 20 which stipulates that “Elementary education shall be compulsory for Jordanians and free of charge in Government schools.” Therefore, on December 20, 2020, Daas created a social media “storm” demanding the return to in-class education with the hashtags “Second semester in school” and “Safe return to school” leading Jordan’s trends on Twitter within less than two hours of his tweets.

Dr. Daas says: “According to the Minister of Education’s statement, 11.5% of students could not access the platform which means that more than 180 thousand students were deprived of their right to education as stipulated in the constitution.”

Education consultant and early childhood expert, Nariman Arikat, refers to the negative impact this educational interruption will have on the psychology of students saying: “This interruption will definitely affect their educational level, may weaken their motivation to learn and cause a deep sense of emptiness. Elementary school children are the ones mostly affected and I expect their educational achievement to be lower than what is required for them to qualify to enter the next stage of school.”

Thinking Outside the Box

In light of this abrupt and complicated situation imposed by the pandemic, several institutional and individual initiatives were launched in an attempt to suggest solutions to help students and their families overcome this crisis. One of these initiatives was organized by the NGO “Ana Ataallam” (i Learn) that launched a national campaign entitled “Darsi Bi Eidak” (My Lesson in Your Hands), which focuses on the refurbishment of older electronic devices and distributing them among eligible families.

Saddam Sayyalah, the person behind the idea, says: “We began work on the campaign in April 2020, by distributing a questionnaire which showed that a large number of parents were unable to provide their children with adequate internet service or the devices they needed to attend classes on the platform. Consequently, we asked institutions and individuals to donate computers, tablets and cell phones which we refurbished and provided one year’s access to the educational platform “Abwab” (Doors), after which we distributed them among more than 1200 families in seven different regions within the Kingdom.”

Dr. Aseel Shwareb, Head of the Department of Educational Sciences at the University of Petra, says: “This is a global issue and Jordan is not an exception. The most important thing at the moment is to make up for the time lost and readjust programs and evaluate each student individually before carrying on with the curriculum.” She called on tutors to “think outside the box” and organize community initiatives that suggest solutions instead of disrupting the educational process awaiting the government’s provision of these tablets.

Lawyer Nasser Hatamleh, Head of the Legal Committee in the Jordanian National Observatory for Human Rights, holds the government fully responsible for providing education to all Jordanian citizens saying: “Because education is free of charge, the Ministry of Education should have found solutions and mechanisms of access for underprivileged students before switching to distant learning. Although this decision affects the constitutional rights of students, no legal action can be taken against the minister since it was issued within the framework of Defence Law no. 13 for the year 1992.

On January 13, 2021, the Minister of Education announced that there would be a gradual return to in-class education for the second semester of the school year, but the outbreak of a new strain of the Corana Virus made parents feel that such a return would be temporary. They were back to square one, struggling, on the one hand, with the decline in their children’s level of education, and on the other hand, dealing with their children’s sense of inferiority as they watch their more privileged colleagues continue to learn and attend classes via the “Darsak” e-platform.

In his policy statement before the 19th Parliament, presented on Sunday, January 3, 2021, Jordan’s PM Bisher Al-Khassawneh emphasized that “the natural learning environment for students is in school,” but warned against the hasty reopening of sectors adding that the return to in-class education would be determined by the epidemiological situation in Jordan. The Premier also said that “the government is working on providing underprivileged students with the required devices and equipment to ensure that electronic learning supports and enhances the development of quality education,” and that the government is “committed to providing educational services to all students fairly and equally.” Shortly after the PM’s statement, the newly appointed Minister of Education, Dr. Mohammad Abu Qudais, announced the continuation of remote learning for the second semester. In the meantime, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship announced that the next tender for the tablet devices would be postponed until further notice. Hence, as the end of the 2020/2021 school year approaches, the inability of thousands of Jordanian students to remotely follow up on their education is an ongoing problem.